Is it possible to ‘design in’ uniqueness?

Protecting the uniqueness of an area could be argued as championing its identity, or at least acknowledging it and responding to it. The appropriateness of any design response in reinforcing the unique character of an area is of course subjective, with approaches ranging from being complementary and sympathetic to being contrasting and challenging. Both attitudes however, still acknowledge the presence of an original identity.

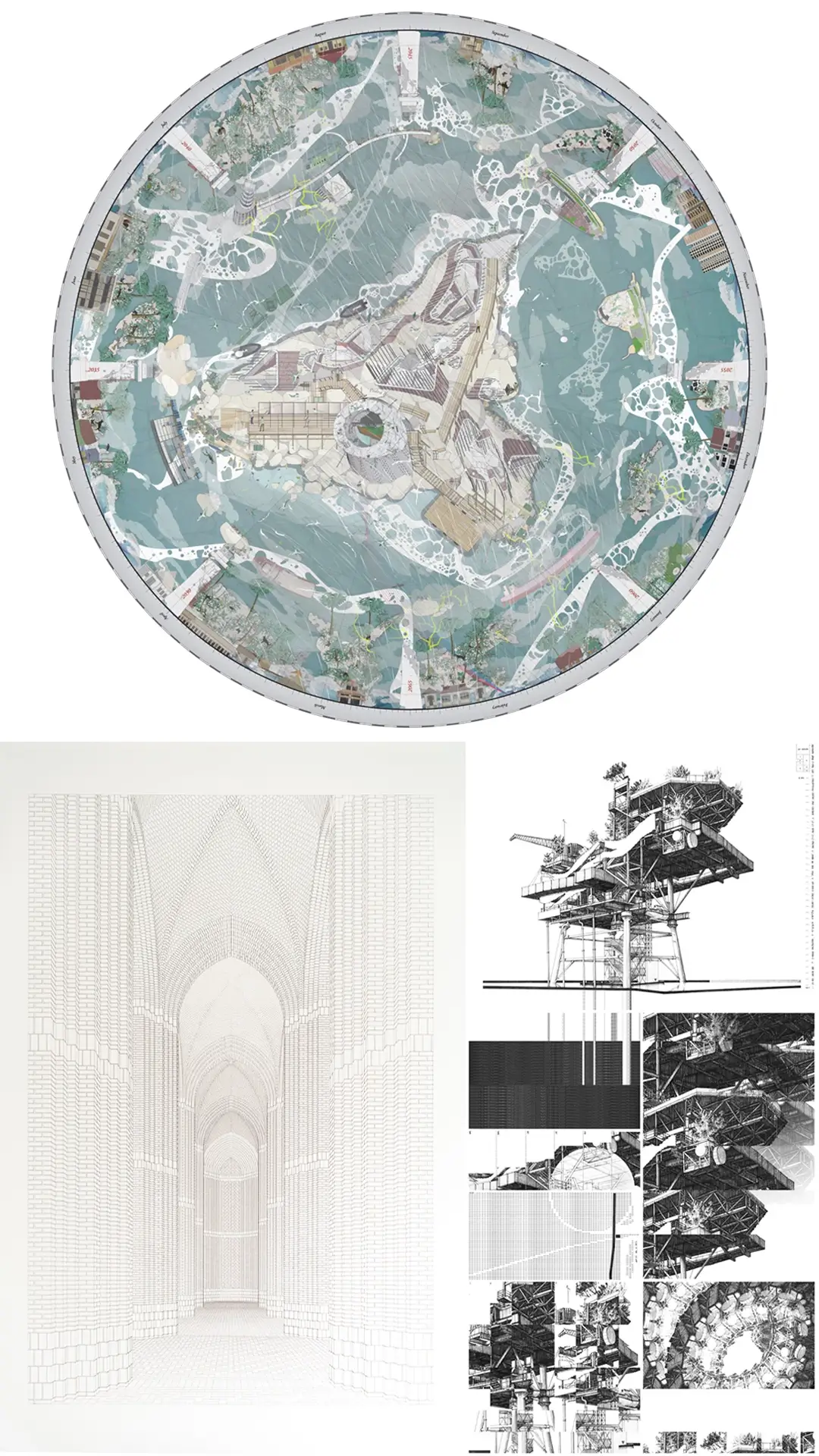

What happens when there is no, or little, conceived present identity from which to respond? What of those times when non-organic growth is unavoidable? This is a more unique challenge for the designer. One could employ a unifying element to the overall project, a kind of rubber stamp to the component parts which points us to the sense of the whole, however obviously. While this might indeed reinforce an identity, it’s hardly the most persuasive argument for uniqueness. In striving to impose a character, there is a danger of crowding out those myriad of possibilities which might appeal to the multitudes of communities who reside there. A more subtle approach might be one of scale. Care and attention should be given to every element of our cities; streets, neighbourhoods, districts and conurbations. Large or small, macro or micro, every scale of our cities serves to form its identity. Surely our own uniqueness is determined by the minutiae of our fingerprints as well as the more obvious characteristics of our facial features? The skill of the designers and planners is to navigate through the various scales with uniqueness of design which in turn enforces the strength of the overall identity.

How then should we approach the ‘design of densification’, so that the city in which these new homes are being built retains its character?

It is a misconception that densification need be the enemy of character. Instead, considered densification should be championed as the preservation of character; it can allow for the protection of the elements of the city which are standard bearers of its identity while allowing the city to survive, grow and thrive. The successful densification of urban areas should allow for the red line protection of those jewels of our cities which we should jealously guard; the parks, the canals, the squares, the notable buildings in which we all stake a common claim.

Densification should not only be protecting the unique areas of our cities, it should also actively contribute to the character of its landscape. Density should not be a simple multiplication of a base unit, the designer should look for opportunities in densification – height offers views and critical mass requires amenities. Density therefore, should equate to a myriad of possibilities, each unique and identifiable.

This essay was extracted from the Future Spaces Foundation report: Vital Cities not Garden Cities: the answer to the nation’s housing shortage?