- Designing for circularity: championing materials re-use at 30 Duke Street St James’s

- For What it’s Worth

- Exploring Thermal Labyrinth Ventilation Systems at the Big Data Institute, University of Oxford

- “Discovering magic in the mundane” – Q&A with Ian Hunter, Materials Council

- Retrofit or Rebuild: Getting the most area for the least embodied carbon

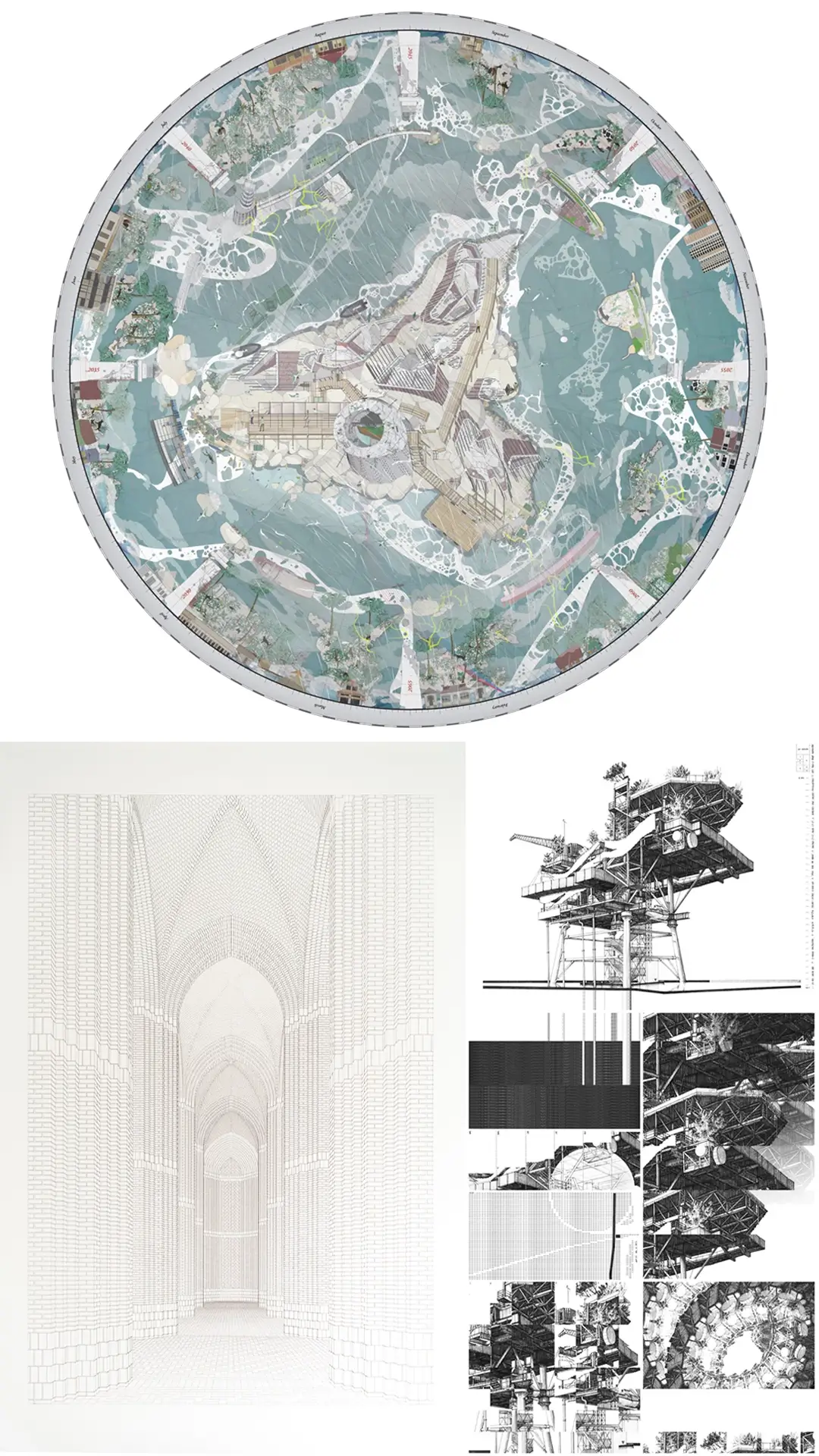

- Winner of The Architecture Drawing Prize 2023: an interview with Eldry John Infante

- Developing in the City: New Build vs Retrofit

- Transforming Cityscapes with the Power of Nature

- Making luxury circular: rethinking re-use in retail fit-outs

- Is it mean to cut down trees?

- “Drawing as a method of dialogical design” – an interview with Eugene Tan

- “I’m interested in intricate and intimate architecture that directly affects people.” – Samira

- Refresh, repurpose, reimagine: Our approach to retrofit

- Developing in the City: New Build vs Retrofit Part 2

- Make models: Carlisle Health and Wellbeing Centre

- AI integration at Make: shaping the future of architecture

- Optimising the value of build-to-rent

- Tall buildings photo essay

- Reflections on Make Neutral Day 2024: Part 2

- Is it green to cut down trees?

- Make models: Station Row section model

- Make models: Drum

- Make models: Milton Avenue/Station Row

- Reflections on Make Neutral Day 2024: Part 1

- Defining a sustainable workplace – the BCO’s climate emergency challenge

- Discussing exhibitions with Dr Erin McKellar, Assistant Curator (Exhibitions), Sir John Soane’s Museum

- “Spirit is pure, so that’s what I feel here.” – Aunty Margret

- Hydrogen: Solution or ‘Techcrastination’?

- Carbon goggles: looking for facades of the future by reflecting on facades of our past

- Winning the 2022 Architecture Drawing Prize

- Variety in urban living: setting the scene

- Make models: Salford Rise

- Variety in urban living: the challenges and opportunities

- Make models: Seymour Centre

- Wilding the City

- Make models: 20 and 22 Ropemaker Street gift models

- Variety in urban living: innovation is key

- Reflections on Make Neutral Day 2023: Part 1

- Designing Regenerative Travel

- Make models: Jersey South Hill

- World Heritage Day 2023 Photo Essay

- Reflections on Make Neutral Day 2023: Part 2

- “Let’s do something a bit different”

- A deep dive into an amazing ‘Wunderkammer’

- Make models: shopping centre competition facade

- “My first subject was a house. From then on, I started developing my drawing skills.”

- The Spirit of Mountain

- Make models: Brookfield Place Sydney

- Make models: community library model

- Q&A with Maker Michelle Evans, project lead on Capella Sydney

- Challenging structural conventions at 80 Charlotte Street

- The power of creativity and experimentation

- Hyperlocal retail post-Covid

- Architectural Drawing: From Soane’s Time to Today

- New business models for a different retail future

- Internet shopping and the effect on cities

- The value of outreach – reflecting on our school engagement with RIBA Architecture Ambassadors

- Pink light veggies

- “I’ve wanted to be an architect since I was four years old.”

- “I’m learning that architectural designs will need to work in the real world.”

- The town centre in five years’ time: Community [1/3]

- Make–ReMake

- Embodied carbon of transportation

- From listed buildings to 21st-century schools [2/2]

- Drawing Sydney

- Inspired by “art built” – an interview with Marc Brousse

- Embodied carbon in curtain walls

- Reducing embodied carbon isn’t all about materials

- “Tall buildings mesmerise me.”

- Make models: metal etching

- “I’m the first one in my family pursuing architecture.”

- “What can you see behind this building?” – an interview with Fe

- My next getaway

- The town centre in five years’ time: Wellbeing [2/3]

- Make models: 80 Charlotte Street

- Living Architecture: Urban Forest

- “I want to build things that will explore new depths of the sea.”

- Upfront carbon: how good is good enough?

- The town centre in five years’ time: For everyone [3/3]

- Winner of The Architecture Drawing Prize 2020 – an interview with Clement Laurencio

- Restoring Hornsey Town Hall’s clocks

- A Proposed Hierarchy for Embodied Carbon Reduction in Facades

- From listed buildings to 21st-century schools [1/2]

- Comparing embodied carbon in facade systems

- Building Natural Connections with Energy, People, Buildings

- Bridging the gap

- Designing in the wake of coronavirus

- Living employment

- Atlas – Tech City statement

- Four ways residential design might change after COVID-19

- Post COVID-19 – What’s next for higher education design?

- Inspiring Girls

- Stephen Wiltshire

- The future of retail and workplace

- Make models: The Cube

- International Women’s Day 2020

- Architectural Drawing: States of Becoming

- One Make

- Post-COVID

- The Architecture Drawing Prize exhibition reviewed

- ‘Architecture in the frame’ – London Art Fair

- A Hong Kong perspective on a post COVID-19 society

- Chadstone Link: Making new connections

- Improving social ties in our cities

- Design narratives and community bonds

- Behind the scenes at the 2019 World Architecture Festival

- Drawing on the culture that makes the buildings

- Future modelmakers 2020

- The City is Yours

- After coronavirus, how can we accelerate change in workplace design to improve connection and wellbeing?

- The Madison model by Theodore Polwarth

- Q&A with our student modelmakers: Theodore Polwarth

- The Teaching and Learning Building model by James Picot

- Q&A with our student modelmakers: James Picot

- Pablo Bronstein

- The Big Data Institute model by Finlay Whitfield

- Q&A with our student modelmakers: Finlay Whitfield

- Encouraging spaces of conviviality

- The importance and passion of heritage in the built environment

- No show, so what next?

- Choosing architectural modelmaking

- World Heritage Day 2020

- Make models: Agora Budapest

- Drawing in Architecture

- Draw in order to see

- Project delivery at 80 Charlotte Street

- Our commitment to sustainable design

- Asta House – Local living in Fitzrovia

- Make models: Chadstone Link

- Transparency and a sense of investment

- Langlands and Bell – Observing and Observed

- Telling Stories: The power of drawing to change our cities

- Musings on The Architecture Drawing Prize 2020

- What role will hotels play in our society after COVID?

- Sketchbooks: draw like nobody’s watching

- Honest, in-depth learning

- Museum for Architectural Drawing, Berlin

- Make models: 20 Ropemaker Street, part 2

- The value of the drawing

- The hand does not draw superfluous things

- Balance

- Prized hand-drawings return a building to an organically conceived whole

- Draw to Make

- Drawing details – technical and poetic

- Betts Project

- Living with loneliness

- Combating loneliness in the built environment

- An update from Sydney

- Retail innovation beyond the shop door: Lessons from the USA (part 1)

- Make models: 20 Ropemaker Street, part 3

- Sydney born and razed

- Retail innovation beyond the shop door: Lessons from the USA (part 2)

- Make models: 20 Ropemaker Street, part 1

- Retail innovation beyond the shop door: Lessons from the USA (part 3)

- Architecture and Creativity

- High-density living in Hong Kong

- Make’s past, present and future

- The Architecture Drawing Prize – Not just another competition

- Leaving a mark

- Community connections

- My time with the BCO

- The call of the wild

- The art of an art historian

- Mary, queen of hotels

- Make models: Portsoken Pavilion

- The Make Charter

- Why Brexit will see a glass half-full emptied

- Make models: LSQ London

- Disappearing Here – On perspective and other kinds of space

- Drawing and thinking

- Drawing to an end?

- Making shops exciting again: Lessons from the Nordics (part 1)

- Make models: Grosvenor Waterside

- Drawing architecture

- The Hollow Man: poetry of drawing

- Above and beyond

- Making shops exciting again: Lessons from the Nordics (part 2)

- Plein air in the digital age

- A “Plan in Impossible Perspective”

- Art Editor’s picks

- Making shops exciting again: Lessons from the Nordics (part 3)

- The future of bespoke HQs

- Make models: The Luna

- World-class architecture

- The Architecture Drawing Prize exhibition review

- The future is bright but not the same

- Employee ownership

- The tools of drawing

- Trecento re-enactment

- Lessons on future office design from Asia Pacific

- The human office

- How drawing made architecture

- Advocating sustainable facade design

- Make models: FC Barcelona’s Nou Palau Blaugrana

- Drawing as an architect’s tool

- Are you VReady?

- Cycle design for the workplace

- The Architecture Drawing Prize

- Make models: an urban rail station

- Reporting from Berlin

- City-making and Sadiq

- Hand-drawing, the digital (and the archive)

- Ken Shuttleworth on drawing

- The green tiger

- Stefan Davidovici – green Mars architect

- When drawing becomes architecture

- Make models: Swindon Museum and Art Gallery

- The role of the concept sketch

- Make calls for a cultural shift in industry’s approach to fire safety

- 2036: A floor space odyssey

- Harold on tour

- London refocused

- Hotels by Make

- Full court press

- Digital Danube

- Don’t take a pop at POPS

- The future of architecture – Matthew Bugg

- The future of architecture – Jet Chu

- The future of architecture – Robert Lunn

- The future of architecture – David Patterson

- The future of architecture – Rebecca Woffenden

- The future of architecture – Katy Ghahremani

- Safer streets for all

- The importance of post-occupancy evaluation for our future built environment

- Put a lid on it

- Designing for a liveable city

- The future of architecture – Bill Webb

- Bricks – not just for house builders

- Designing in the City of Westminster

- Rolled gold

- How to make a fine suit

- Responsible sourcing starts with design

- Is off-site manufacture the answer?

- Developing a design for the facade of 7-10 Hanover Square

- Curious Sir Christopher Wren

- Responsible resourcing should be an integral part of every project

- The socio-economic value of people-focused cities

In 1915, Gunnar Asplund and Sigurd Lewerentz (1885-1975) submitted a single competition entry for a new woodland cemetery in Stockholm, Sweden. It comprised a vast and intricate site plan in which each individual pine tree was inscribed on the drawing, peppered with towers, chapels, crematoria, clearings, and avenues. Borrowing from myth and Nordic folklore, the proposal reflected on—and subsequently defined—the nation’s attitude to death and remembrance.

To realise Skogskyrkogården the architects moved heaven and earth. New, if not subtle, approaches to cosmic symbolism were established and shaped in brick, mortar, stone and wood, while earth itself—the very mass of the landscape—was excavated and recast to form a gentle, undulating topography of interlocking forests, vistas, and ritual sequences. While many of their original ambitions were lost to years of incremental refinement, one chapel—Lewerentz’s Uppståndelsekapellet (Chapel of Resurrection)—represents the spirit of an imaginative synthesis of northern aesthetic traditions and burial practices in the context of a rapidly modernising world.

The Way of the Seven Wells, a long axial pathway that stretches from an elevated elm grove to the Uppståndelsekapellet, is among the few gestures that survived the (often brutal) iterative design process. While the wells themselves were never completed, the pathway forges a long, processional avenue from the entrance of the cemetery to the freestanding canopy of the chapel; a direct line of movement, sided by a tall wall of pine trees, sheltered from open sunlight and the slightest breeze.

In a 1923 drawing, Lewerentz—or, some maintain, his sometime collaborator Kurt von Schmalensee (1896-1972)—sought to articulate the complex spatial arrangement that sprung from the termination of the Way of the Seven Wells and the spaces—both interior and exterior—that make up the chapel. Described by one researcher as a “plan in impossible perspective”, by another as “Lewerentz’s naivistic [sic] drawing”, and by most as merely a “site plan”, the drawing is in fact a logical representation of an intricate and symbolic orchestration of funerary movements.

For most services that take place in the Uppståndelsekapellet the deceased arrives by way of the road that slices this drawing horizontally, intersecting the Way of the Seven Wells. From here, gathered mourners assembled in the enclosed square adjacent to the chapel, prior entering. Or, in case of rain and snow, beneath the Pillar Hall or in Lewerentz’s waiting room – a later addition, positioned on the site of the semicircular clearing. Once the first phase of the service is complete, the deceased and their mourners exit the space by way of a second door on the western side of the building, descending a shallow staircase toward the place of internment.

In this drawing, an entire pattern of sequentially interwoven rituals and movements are penned with remarkably precise representational language. Landscapes—contained, compressed, and open—are articulated with implacable functionalism while, at the same time, reference an entirely unique and highly nuanced corporate understanding. In this way, the drawing is in itself a masterful example of the rich conceptual potential of the architectural drawing.

This post forms part of our series on The Architecture Drawing Prize: an open drawing competition curated by Make, WAF and Sir John Soane’s Museum to highlight the importance of drawing in architecture. The winning and shortlisted drawings are being exhibited at Sir John Soane’s Museum 21 February – 14 April 2018.