So when we draw by hand, we do so reaching out to the environment around us, and in doing so, says Hewitt, “We experience sensory and cognitive ideas concurrently.” The brain, “is not merely a circuit board that processes zeros and ones like a computer chip; it is also a supporting actor in a complex network of organs, nerves, chemicals and electrical signals that we know as the human organism.”

Hewitt’s plea, rooted through hand drawing – for “drawing as a medium of thought”, a “loop between biological memory and external memory” – is for a humanistic architecture all too often lacking in an era when “novelty and originality are ultimate tests of artistic worth”, when architects, often tied to a computer, feel the need, or pressure, to write and speak in arcane jargon to explain what a pencil drawing by Brunelleschi, Michelangelo, Alvar Aalto or Louis Kahn could do without a word of theoretical explanation.

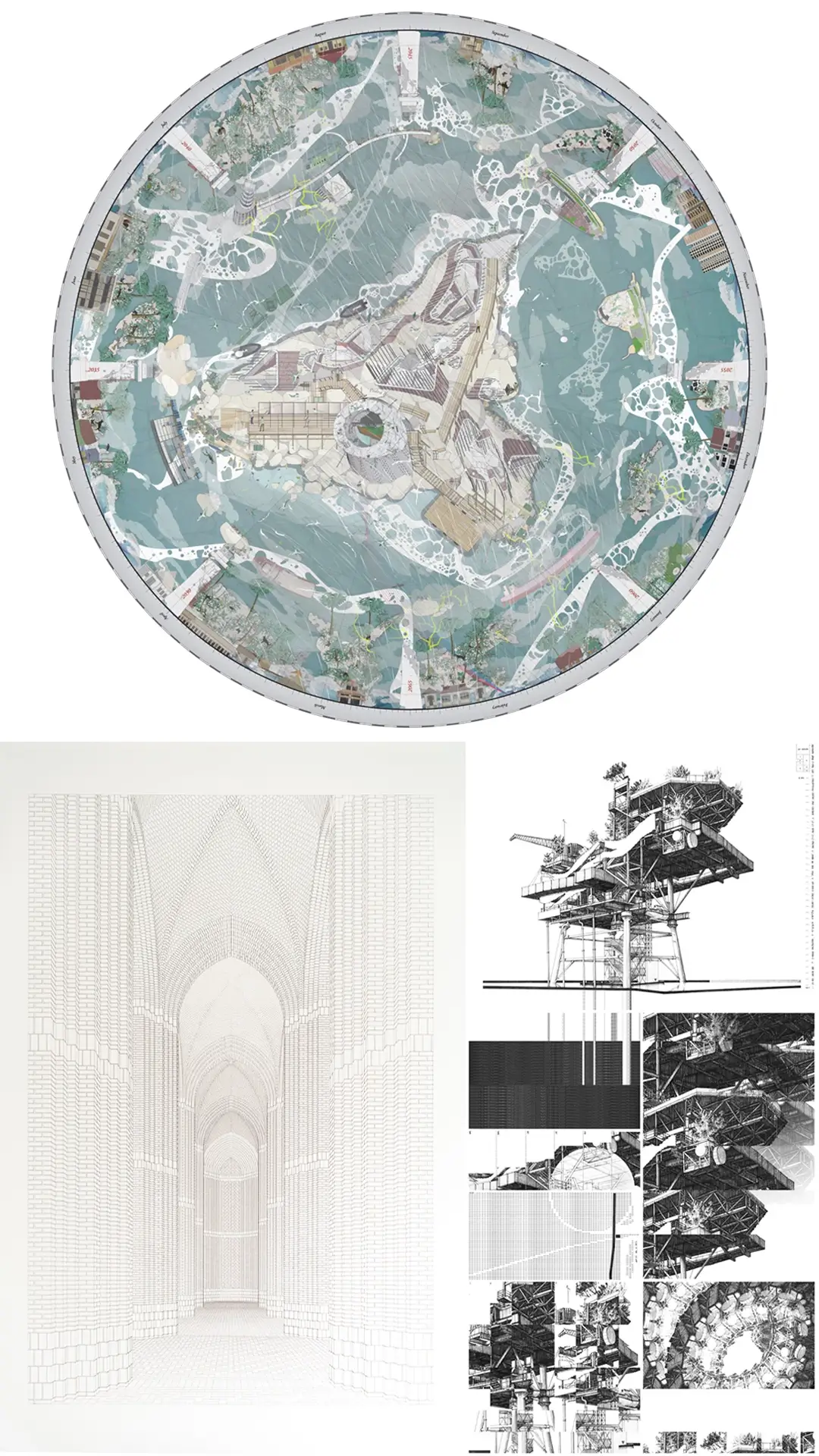

The Architecture Drawing Prize 2020 encourages digital, hybrid and hand drawings, yet, significantly in the light of the Covid-19 pandemic, there will be a “Lockdown Prize” for a drawing completed during the lockdown or relating to the changes that Covid-19 may, or will, bring to architecture. During lockdown, many architects have turned anew to hand drawing, sketching objects, rooms, people, pets and plants around them, learning as if all over again how to reconnect with that “loop” identified by Mark Alan Hewitt “between biological memory and external memory.”

To draw by hand, as Hewitt points out, is not to regress in terms of architectural adventure. He reminds us how Frank Gehry’s radical Bilbao Guggenheim was the creative product first of hand sketches and hand-made cardboard models and only in the production stage, a design fed into computers. And he traces this tradition back to the masters of Baroque architecture who worked at a time when hugely imaginative buildings were the memorable product of embodied knowledge – ways of conceiving and making daring buildings handed down over centuries – and experimentation made through drawings that do indeed reveal hand and eye, mind and body working together.

Hewitt talked with Harley Jessup, the production designer for many of Pixar’s digitally animated films. His studio made 28,244 hand drawings for Toy Story 2, 46,024 for Monsters Inc and 72,000 for Rataouille. Jessup wants his designers to see and this means drawing by hand. Computers have their own wizardry, yet truly humane design and architecture need that embodied knowledge and sensory experience that comes from picking up a pencil and making marks on paper.

Draw in Order to See: A Cognitive History of Architectural Design by Mark Alan Hewitt, Oro Editions, 2020, £29.95

This article was originally published on ArchDaily.

This post forms part of our series on The Architecture Drawing Prize: an open drawing competition curated by Make, WAF and Sir John Soane’s Museum to highlight the importance of drawing in architecture. Entries for 2020 close 2 October.