Students speak

As we continue our examination of higher education design, it would be remiss of us not to ask students their views on the campuses of the future. We talked to students, recent graduates and alumni from the Stephen Lawrence Charitable Trust in London, as well as Hong Kong University and University of Sydney, asking them the same questions we asked our own architects, all of which are inspired by interviews we’ve done with international thought leaders in the field. It’s interesting to see how the students’ thoughts compare with those already working in the industry, especially their hopes for how campuses can evolve to be more inclusive and sustainable, with an emphasis on collaboration and engagement.

“When there is no defined boundary, a campus can open up and connect itself to the urban space.”

Chunyan Lim, Second-year Master of Architecture student at the University of Sydney

How can city campuses become part of the city and not just in the city?

Openness and permeability are the key to integrating city campuses into the urban fabric. This is something I realised in the course of my studies at the University of Sydney. In my personal experience, USYD is a great example of how a city campus can be interwoven with city life. Coming from the direction of Redfern Station on my first visit, I was greeted by a row of bamboo trees that led me to Cadigal Green. I didn’t even realise I’d reached the campus until Google Maps informed me.

When there is no defined boundary, a campus can open up and connect itself to the urban space. It struck me that Cadigal Green is not simply part of the campus but more like a public space that serves students, staff and the neighbouring community. The huge lawn area slopes towards the Old School Building, which acts as the focal point.

It has been fascinating to observe the multiple uses of this green space. In the morning, the wide promenade becomes a shortcut for those commuting to City Road or Redfern Station. In the afternoon, the lawn and S-shaped benches are a favourite lunchtime spot for both students and staff. In the evening, you see locals walking their pets, kids running around, and friends relaxing and chit-chatting. On weekends, there are family barbecues. The most exciting time is summer break, when outdoor film screenings are held in the evenings with beanbags on the lawn.

Cadigal Green is surrounded by a gym, library, café and even a bubble tea shop, all of which help bring liveliness to the area. It’s my favourite spot to relax after a workout at the gym. By opening up the campus and increasing its permeability to the public, there’s more opportunity for creative use. This not only merges the campus with the city but also enriches campus life beyond just study.

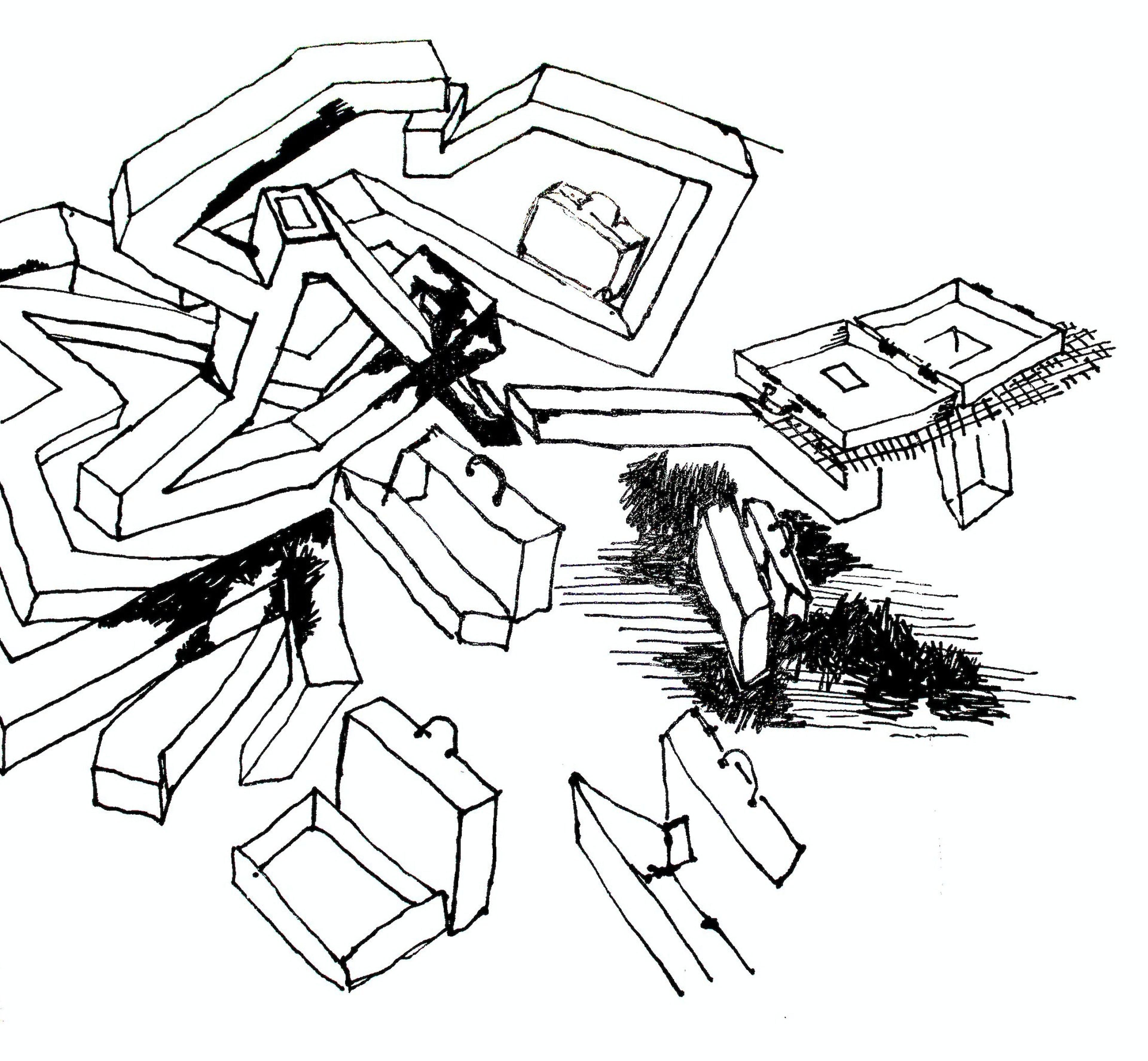

Cadigal Green, USYD

by Chunyan Lim

Simone Carmody, final-year Bachelor of Architecture and Environments student at the University of Sydney

How can universities design in flexibility to respond to changes in course popularity and how students are taught?

The way students are learning, as well as the courses they are choosing to pursue, is a direct reflection of our rapidly changing world. It is no surprise that students are choosing courses that offer opportunities to be leaders of change, enabling them to make a positive impact in a world seemingly plagued by bad news.

Many courses are shifting to incorporate interdisciplinary approaches, providing students with a wide range of skills that enable them to adapt to the changing world. We are increasingly seeing the necessity of collaboration between disciplines to tackle shared challenges.

Many students are no longer contained to a cookie-cutter curriculum. Instead, they have opportunities to cater their education towards individual career interests and goals. It would be in the best interest of universities to consider these new ways of learning in their teaching environment, designing flexible campuses that can embrace change.

As learning environments have changed to be exclusively online, questions around the future of the campus arise. Are the days of the lecture hall gone? What comes next for face-to-face teaching?

Some faculties hope for a post-pandemic return to ‘normality’; however, I believe these times have presented us with opportunities to rethink ‘normal’. We have adapted to working and learning from home, transforming the purpose of our built environment through technology.

Similarly, the university campus has to adapt to its changing purpose through flexible design. If we are able to repurpose our dining tables into classrooms, imagine what designers could achieve by repurposing the campus to embrace new technology and collaborative modes of learning.

A particular realisation shared by students throughout the past semester is that for many classes, the experience of sitting in a lecture hall is unengaging and outdated. If participation is not mandatory, the turnout of students is low, with many opting to watch lecture recordings online even before the pandemic struck. Being comfortable during Zoom lectures has ultimately led to a higher engagement from students.

In some cases, the rigid architecture of lecture halls can cultivate an environment of intimidation for both teachers and students. As versatile courses increase in popularity, collaborative spaces become more in demand. The inflexibility of the lecture hall may be a detriment to its future as the platform for face-to-face teaching.

It is vital now more than ever for universities to learn from this past year. Embracing flexible design in learning modes, teaching policy and the built environment solves current issues and prepares for an uncertain future.

“If we are able to repurpose our dining tables into classrooms, imagine what designers could achieve by repurposing the campus to embrace new technology and collaborative modes of learning.”

“They should connect to other city buildings like pubs and public libraries, creating a labyrinth that smudges the lines separating learning spaces and public spaces.”

Georgina Larbie, alumna from the Stephen Lawrence Charitable Trust

How can city campuses become part of the city and not just in the city

When I think of this, I personally think of my own university location, which I suppose most students would do. Brighton, composed of two universities and a beach, is the epitome of a ‘uni town’ – a good setting for a coming-of-age novel. The University of Brighton has three campuses spreading from the seafront to Falmer, the edge of the student-led abyss, while Sussex University hovers even closer to the edge, with its own pubs, accommodation, Co-op and post office. The latter is practically its own self-reliant ecosystem of learning and achievement. It is in no way part of the town; it’s merely part of the bus route.

Numerous universities are a town within themselves – they want for nothing, so the cities that surround them don’t have a place in their ecosystem. My immediate response to any attempt to blur cities and the universities they contain is to suggest disrupting where university buildings physically end. They should connect to other city buildings like pubs and public libraries, creating a labyrinth that smudges the lines separating learning spaces and public spaces.

This discussion hints at the general boundaries drawn between universities and the general public. University libraries, pubs and lecture theatres are not for the public. In the UK, higher education has a £9,000 gatekeeper, and this is reflected by the fact that the general public can’t just walk into the spaces students risk debt to occupy. Likewise, students can’t take two steps away from their tutors and suddenly be in their favourite shop. Boundaries work both ways.

Architecture and town planning are often representative of current social settings and economic values. In this case, higher education sits on a pedestal. A university library is more thorough and diverse in content than a public library, but why? Because only university students should have access to a wealth of knowledge or specialist equipment? Why should the general public be at a loss while 18 to 25-year-olds are enabled (for the length of their degrees, anyway)?

For campuses to become part of a city and not just in that city, we must build fewer walls and instead integrate campus buildings throughout towns. Clustered buildings discourage connectivity between a university’s private spaces and the very public nature of cities. Perhaps we should rethink what a university even means so that it can be something not just to students but also to Joe Bloggs, his wife and his child.

Attempting to Connect Spaces

by Georgina Larbie

Shanae Boisson, alumna from the Stephen Lawrence Charitable Trust

How can universities design in flexibility to respond to changes in course popularity and how students are taught?

To futureproof higher education, we must design integrated spaces where different faculties are no longer separated. By easing access between different subject areas, students will encounter more topics outside of their chosen course, in turn broadening their knowledge and critical thinking skills.

We must also design built environments that enhance individual methods of learning. While mixed-use space is one approach, a new typology is necessary to truly open students’ minds, enable them to see the bigger picture and inspire innovative thought. One example is Neri Oxman’s MIT Media Lab in Massachusetts, a cross-disciplinary setting that interlaces technology, media, science and art. Students here work together as a collective, solving real-world problems.

As the world advances, curricula must also advance, with greater consideration given to the courses provided to future generations. Incorporating more public spaces within educational environments would help ensure students aren’t shut out from the outside the world. The outside world and the academic built environment should not be treated as separate entities.

It’s one thing to attract talent but another to lose talented individuals, even though they have the right level of skill and ability, because they didn’t feel the environment was right for them. You cannot expect students with diverse interests and talents to excel equally in the same environment. As Albert Einstein famously said: “If you judge a fish on its ability to climb a tree, it will live its whole life believing it is stupid.” Individuality should be celebrated, with the academic built environment tailored to enable students to fully express themselves.

Throughout 2020, students have demonstrated remarkable adaptability all over the world, with many successfully completing their academic year virtually from their bedrooms, often alongside family members also working from home. This is an indicator that we no longer need just one ideal for the academic built environment, especially in the digital age, where we are not confined to physical space.

This could be the end of overcrowded courses and vast building footprints that hold a limited number of students. With more choice and flexibility to the environment in which they carry out their studies, students have been able to approach their lives more holistically. They’ve been reminded that they are more than just students, that there is life outside of education and that their wellbeing matters. As individuals, they have found balance and discovered themselves.

“While mixed-use space is one approach, a new typology is necessary to truly open students’ minds, enable them to see the bigger picture and inspire innovative thought.”

“I felt set apart from the world, even though I walked through the city to my campus every day.”

Vincent Lo, Master of Architecture student at Hong Kong University

How can city campuses become part of the city and not just in the city?

Universities are often seen as prestigious institutions where highly educated people attend courses to refine their skills and knowledge within a specific aspect of interest. These people in return fuel society by strengthening various fields of study and boosting industries’ human capital.

With such large contributions to cities by university graduates, it is only fair that cities give back to their universities. The city typically reserves large prime plots of lands for building these institutions, but being physically located in a city does not mean a university is necessarily intertwined with its daily routine. One aspect I myself as a university graduate have experienced is a lack of an exterior intervention during my course of study. I felt set apart from the world, even though I walked through the city to my campus every day. The only external connections I had were with people from practices who came in to give talks. The things I learnt were not directly applicable to the world of real practice.

I think mixing up public places and university campuses to combine the two could help address this, allowing both sides to coexist, observe each other’s daily lives, and experience a small yet direct taste of each other’s existence and contributions to society. For example, a city could invest in a cutting-edge cancer research lab, with the city’s best firms locating their scientists there while students from local universities work side by side on their own projects. Students could keep their distance to avoid obstruction, but still operate enjoy occasional collaboration in terms of talks and knowledge sharing.

This could work with other industries too – architects and their studios, pharmaceuticals and their drug labs, lawyers and their courtrooms, and more. With some more thought and refinement, I believe this idea could be implemented with success and have a surprisingly positive impact on society.

Publication

This article appeared in Exchange Issue No. 3, a look at how the COVID-19 pandemic has influenced the future of university design, featuring insight from chancellors, architects, students and more.

Read more